Too Subtle

Writing a thriller with dual protagonists (in my case, Tobie and Jax) presents several difficulties, many of which fall under the general heading of “point of view.” For those of you unfamiliar with the writers’ expression “point of view” or POV, it simply refers to whose head we’re in. In other words, are we as readers experiencing the action from Tobie’s perspective or from Jax’s perspective? If we’re in Tobie’s perspective, we see what she sees, hear what she hears, and know what she’s thinking and feeling. She can only guess what’s going on in Jax’s head. Writing is all about choices. And one of the reasons POV is troublesome when you have two equal heroes is because the writer has to decide, Okay, whose POV am I going to write this scene from? In some cases the choice is obvious. At other times, less so. And how do you remind readers whose POV they’re in—particularly in a fast-paced book without a lot of introspection? I always have some sort of clue at the beginning of each scene to let readers know whose POV we're in. But because of the nature of the books, those clues are often very subtle. So I also decided from the very first book that Tobie would think of herself as “Tobie” while Jax thinks of her as “October.” Ironically, I never told my coauthor, Steve, I was doing this—I just assumed he’d noticed. I mean, he’s read each of these books over and over again, right? Well, I came right out yesterday and asked him if he’d realized that Jax always thinks of Tobie as “October” so that it’s one way to tell who is the POV character in any given scene. He stared at me blankly and said, “Really? I never noticed.” So now I’m thinking, if Steve hasn’t noticed, I doubt anyone else has, either. Although I’d like to think maybe readers notice subconsciously. No? Oh, well; at least it serves to remind ME whose head I’m supposed to be in. Labels: point of view, writing

Are You Visual or Aural?

Can the way we like to learn also influence the way we write and the kinds of books we like to read? This interesting concept was suggested to me by Sabrina Jeffries, a NYT bestselling romance writer who recently visited our Monday night writers group (she was in town visiting her agent and critique partner of many years, both of whom are members of the group). She said she was an aural learner, and she thought that’s why she didn’t like putting a lot of visual description in her books and becomes inpatient with writers who do. (She also said where she picked up this interesting concept, but I was so focused on the idea itself that I didn’t hear that part.) It’s an intriguing idea. I Googled learning styles and discovered that, yes, our preferred learning styles do influence more than just they way we prefer to study. They also affect the way we internally represent experiences, the way we recall information and the words we choose. So it makes sense that they would influence the way we write and whether or not we like James Lee Burke. There are actually several different approaches to learning: Visual (spatial): prefers using pictures, images, and spatial understanding. Aural (auditory-musical): prefers using sound and music. Verbal (linguistic): prefers using words, both in speech and writing. Physical (kinesthetic): prefers using body and sense of touch. Logical (mathematical): prefers using logic, reasoning and systems. Social (interpersonal): prefers to learn in groups or with other people. Solitary (intrapersonal): prefers to work alone and use self-study. Although we usually have a dominant learning technique, most people use a combination of these approaches. The same person can even use different styles in different situations. My kids, for instance, learned better when they could move around (works great for memorizing spelling words at home, but not so good in a classroom situation when everyone is expected to sit down). My daughter also discovered she could remember her French vocab words if she wrote them on colored cards: blue for masculine nouns, pink for feminine. But our styles are not fixed; we can develop our abilities in our less dominant styles. And each of these styles uses a different part of the brain, so the more areas of the brain we use when learning, the better we remember. I guess my exercise with the colored note cards shows that I’m very visual. My card system also betrays that I’m very logical; I like to diagram things out and classify information. But I’m also highly aural: I remember material I hear in a lecture better than I remember what I read, just as I learn the words of songs or poems I hear very quickly. Unfortunately, I am not at all kinesthetic; when my girls and I were taking Tae Kwan Do, they’d learn our belt pattern the first night and then spend the next three months trying to drill it into my thick head. I’m also a solitary rather than a social learner: no study groups for me. How about you? How do you think your personal learning style influences your writing or reading? Labels: reading, writing

Confessions of a Plotter

Whenever anyone asks if I plot my books in advance or simply fly off into the misty unknown and write by the seat of my pants, I always say, “Oh, I’m definitely a plotter.” But that doesn’t mean I have every scene nailed down before I start writing. I do carefully work out the beginning and sketch in the end (the operative word there is sketch). But my ideas for the middle are usually just that—ideas for scenes that sort of float, well, in the mist. And there usually aren’t enough of them. I’ve learned over the years that my grasp of the story changes once I actually start writing and new ideas pop up, so it’s a waste of time to put too much effort up front into carefully laying down a path I won’t end up following. But I can only go on like that for so long. Somewhere around page 75-100, I haul out my 3x5” cards and go to work on my plot again. Each card represents one scene. The note cards I use at the initial concept stage—when I’m just getting a rough idea of what will happen for the proposal—are all white. But once I’m well into writing the story, I get really obsessive about pacing and timing. And since I’m a visual kind of person, when I go back and attack my plot again I use colored index cards. If you’re curious about what all those different colors mean, here’s the code for my thrillers (I take a different approach for my mysteries): Light green: Tobie and Jax scenes Light blue: Noah scenes (Noah is the protagonist of the interwoven subplot) Purple: action scenes involving Tobie and Jax (i.e., chases, fights, shootouts, etc.) Dark blue: action scenes involving Noah Dark red: the head villains plotting the dastardly deed Jax and Tobie are racing to avert Light red: the villains’ minions, maneuvering to get Jax and Tobie (or Noah) Yellow: missing links—places I need something to get me into or out of a scene or sequence of scenes The beauty of this system is that I can see everything—pacing, character flow, and missing links—at a glance. I can see I need a purple card (a fight or a chase) here, or that I go too long without a villain scene there, or that I need another blue sequence with my subplot character, Noah, in there. The layout is significant, too. But for now, I’ll leave you snickering at my OCPD tendencies. Labels: Plotting, writing

Back on Track

Well, I finally finished the reworking of the first hundred and twenty pages of The Babylonian Codex. I sat down last night and read through it. The pacing is good and the action tight, so all systems are now go to chug forward again. I had a brief moment of panic when I couldn’t find my outline for the rest of the book. That outline—much scribbled over after Steve and I spent several nights intensively replotting—still isn’t finished, but the thought of losing the progress we’d made had me sick to my stomach. I spent several frantic hours cleaning up my office and my bedroom (I do a lot of my writing perched on the porch swing of the upstairs gallery). On the off chance I'd somehow mixed it up with my research material, I even sorted through and filed a huge stack of notes and print outs on everything from sailboats to the Gospel of St. Thomas (at which point I realized I’ve done way too much research for this book). I even went through the trash. And still no luck. Of course I found it sitting on my desk, stuffed in the back of a note pad but so well aligned that nary a hint of its presence showed. I swear I looked in that pad a dozen times. Note to self: become more organized, or risk stroke. Labels: Plotting, writing

Gratuitous Laughter

I don’t have a very high opinion of gratuitous sex and violence in either books or film--with “gratuitous” defined as scenes that do nothing to advance the plot but are there simply because sex and violence have broad appeal. But what about gratuitous laughter? Ah, now that's different. There actually is such a thing as non-gratuitous humor, where the humor comes from the plot line itself. But much humor is gratuitous—a situation or gag stuck in the story just for laughs. Take it out and the plot would run along fine; it just wouldn’t be as funny. I pondered all of this while watching the recent Star Trek movie over the weekend. SPOILER ALERT. Take, for instance, the scene where Bones gives Kirk a vaccine that makes him sick in order to get him onto the Enterprise. That scene is necessary to move the plot forward. What is not necessary is that Kirk has a reaction to the vaccine; that complication exists solely to inject humor into the scenes that follow. Likewise the scene where Scotty and Kirk materialize on the Enterprise and Scotty finds himself in some sort of cooling system. Again, that complication is played out solely for laughs, to make their arrival on the Enterprise more interesting. In fact, one could argue that it's the humor that makes this movie enjoyable to watch; like The Voyage Home, this Star Trek movie goes for the laughs. Yet while gratuitous humor does not bother me, it occurs to me that the word complication could actually be used to describe the gratuitous scenes of violence that I find boring and annoying. So perhaps the truth is that I simply have more patience for humor than I do for violence? Hmmm… On a side note, We got rain! Labels: writing

Make Up Your Minds Already!

Going over copyedited manuscripts always puts me in a cranky mood. Going over two copyedited manuscripts, one right after the other, when I can hardly think straight thanks to the flu has put me in an ubercranky mood. (So you’ve been warned.) Now, I’m not one of those writers who see copyeditors as the enemy. I know I do incredibly stupid stuff when I’m writing. When my brain is flying along in creative mode, I write ‘sat’ when I should use ‘set,’ and ‘discrete’ when I should use ‘discreet,’ and a dozen other strange permutations of the English language. A car that is black in one chapter suddenly becomes red. A character named Yates suddenly becomes Yardley. And no matter how many times I go over a manuscript, I still miss those pesky little mistakes. Lots of them. So thank god and publishers for copyeditors. But there’s nothing like going over two copyedited manuscripts back to back to make you appreciate that this is not an exact science. I feel like screaming, Okay, guys! How about if y’all get together and make up your pedantic little comma-obsessed minds? Do we say: Now, she knew she was wrong. Or do we say: Now she knew she was wrong.Because you see, if it’s so important that you guys feel the need to take out a comma—or put it in—then shouldn’t you all agree, especially since you claim to be using the same style guides? Obviously not. Or here’s another one/Or, here’s another one: What I want to know is, Do I capitalize the D? Or should I say, do I capitalize the d? One copywriter says, no. The other says, Yes. Ghrrr. And don’t get me started on capitalization. Back in the dark ages when I went to school, if you wrote, “the Secretary of State [as in, Clinton] walked across the room,” the office-as-placeholder-for-the-name was capitalized. But it seems that in the decades since, newspapers discovered that such capitalizations slow down their readers, so they stopped using them. Now (,) everyone (including certain New York publishing houses) is following the newspapers’ lead. The problem with that approach is that if you have a character who is constantly referred to as “the Colonel” or “the General,” then I think it’s less confusing for readers if the old rule is followed. So I have stuck to my guns on this one. But believe me, it’s exhausting. As in parenting, one must pick their battles. Now (,) you might think I could just jot down some notes about house rules and make the effort to have my next manuscript conform. But apart from the fact that I don’t need one more distraction, these aren’t house rules; these are individual copyeditors’ rules. I looked up previous manuscripts. And you know what? I started sticking those bloody commas in after the “now” and the “once” because a previous copyeditor with the same house insisted they were needed! So, I give up. Or is that, so I give up? Or should I have said, Or is that, So I give up? Or… Labels: copyediting, writing

Don’t Go Down in the Basement. Then Again, Maybe…

We’ve all had those moments. We’re watching a thriller/horror movie. It’s dark. Evil people/spirits/creatures are aprowl. Our pretty young thing hears a noise down in the basement. Does she go for help? No. Does she run like hell? No. We’re screaming, “You idiot! Don’t go down in the basement!” But does she listen? No. She goes down in the basement. Why do writers do this? Frequently it’s because they’re lazy. If our heroine calls the police and says, “I think there’s a prowler in my basement,” there goes our writer’s scary/gruesome scene. It’s a lot easier to get an unbelievably stupid character into trouble than a smart one. That’s not to say that smart characters can’t make mistakes and get into trouble. Everyone makes mistakes, especially when they don’t have all the necessary information or if there’s something in their past that is driving them to make bad choices. Or maybe our character has a choice between a bad alternative and a worse alternative—say, she hears her baby crying down in the basement. Then she has my sympathy and respect when she goes rushing down into trouble. But those kinds of situations are a lot trickier to set up. They’re more work. (And even then some opinionated reader will probably criticize your character for making a poor decision.) Yet I’m beginning to suspect that there are a lot of readers/viewers out there who don’t actually care if their hero—or at least their heroine—does the equivalent of going down in the basement over and over again. Consider, for instance, a certain megaselling series, which is sort of like Buffy the Vampire Slayer only without the kick-ass heroine (I always thought Buffy’s snap kicks and knife hand blocks were a big part of her appeal, but then, what do I know?). Rather than dispatching her enemies with Tae Kwon Do and a stake and a humorous quip, the heroine of this megaseller goes down in the basement over and over again, largely so that she can be rescued by her hero. I don’t think this is an example of lazy writing. This is deliberate. In a sense, it’s a retreat to an earlier age, where the damsel was in distress and the hero saved the day. And readers love it. One out of five books sold in the United States in the first quarter of this year were by this author. One might actually deduce that its heroine’s propensity to go down in the basement is an important part of this series’ appeal. Is that true? I don’t know. If you’re a fan of this series, please don’t think I’m criticizing it, because I’m not. This author has obviously tapped into something huge here. I’m just trying to understand it. Labels: characters, writing

Hello, April!

I don’t know about you, but I am really glad to see the back of March. In the past month I have: finished my fifth Sebastian book, What Remains of Heaven; seriously injured my eye; slogged (one eyed) through my editor’s requested revisions on my second thriller, The Solomon Effect; lost one of my cats; caught a nasty case of bronchitis that provoked a porphyria attack; and slogged (bucket within reach) through massive editorial rewrites for What Remains of Heaven. I’ve also participated in the presentation of an all-day workshop for aspiring writers at our local Barnes and Noble; had my youngest daughter home for spring break, and presented a luncheon speech at the Metairie Literary Guild. I started plotting my sixth Sebastian book, tentatively entitled What the Dead Tell (I know I won’t be allowed to keep that one), and then, yesterday, I sat down in a white heat and wrote the first chapter. Coming up this month, I need to finish nailing the plot of the Sebastian book and write the first 35 pages and synopsis; plot the third thriller and write that proposal; and participate in the Jubilee Jambalaya conference down in Houma, where I’m presenting a workshop on plotting. It’s still a lot to do, but this is the part of writing that I love. Unlike (cue morgue organ) the dreaded edits. Why do I hate edits so much? Because at that point, almost every book I’ve ever written strikes me as a piece of cr*p. I am painfully aware of the story’s warts and weaknesses. But time (or my own talent) has run out: this is as good as it gets, and as far as I’m concerned, it’s never good enough. But the proposal stage (cue bird song and time elapse photos of spring flowers unfurling) is a time for falling in love, when my story idea is still a bright shiny bauble toward which I reach with excitement and wonder. There is no book, only an idea, and as we all know, falling in love with an idea is so much easier than loving a reality! Labels: edits, Plotting, writing

“I Can See Russia From My House!”

No, this isn’t a blog about politics. But I do intend to use politics to make a point about something. Marketers work very hard to come up with tag lines that can be used to “brand” products. But sometimes this branding happens spontaneously, and I think we could learn something by looking at how and why that happens. Think about the way in which presidents, vice presidents, and candidates are so often branded, for good or ill, by one telling phrase. For Nixon, it was (cue lowered eyebrows, shaking jowls, and guttural voice) , “I’m not a crook.” For Reagan, “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!” (Reagan was lucky; if Afghanistan hadn’t crashed the Soviet Union, Reagan’s defining line would probably have been the endless dazed “I don’t remember” from the Iran-Contra hearings.) Clinton? Take your pick: “I did not have sex with that woman.” Or, “That depends on what the meaning of is is.” Bush II? “You’re doin’ a heck of a job, Brownie!” (closely followed by Mission Accomplished and “Bring it on.”) Think about Dan Quayle and what comes to mind? Potatoe.” Hart? The Monkey Business. These politicians did not choose these phrases as their defining tags; the media and the public chose for them. Why? Because for some reason, these phrases resonated with people. We see this sort of thing happen with movies, too. Think about Make my day. I see dead people. Show me the money. You had me with hello. Why do these phrases become so iconic? I don’t know. It doesn’t seem to happen as often with books. True, most people would recognize the first line from Pride and Prejudice. Gone with the Wind gave us three lines: As God is my witness I’ll never be hungry again, Tomorrow is another day, and Frankly, dear, I don’t give a damn. But were those phrases so well known before the movie? I don’t doubt there are other examples from books, but it says something that I can’t think of them. Still, I suspect we could learn something important by studying these phrases and thinking about the way they click. So, thoughts, anyone? p.s. I know Sarah Palin actually said you can see Russia from Alaska. But because Tina Fey’s line so wonderfully captured the essence of the absurdity of the original, that’s the phrase that will forever characterize Palin (that and the turkey massacre). Labels: marketing, writing

Back to Work, Or, Oh My God I’ve Less Than Two Months to Finish This Book!

Well, it’s a new year, and I’m back at work after more than three weeks off. I haven’t been anywhere. But sometime in early December, when my youngest was home from college and I realized my tree wasn’t up, my house wasn’t decorated, and I hadn’t bought any Christmas presents, I decided I had two choices: I could either keep trying to write my book and end up resenting Christmas and making my family miserable, or I could take off my writer’s cap, put away my manuscript, and just enjoy the holidays. Christmas and my family won. I had a great time, and I hope my family did, too. Last Friday I put my youngest on a flight to Italy. I spent the weekend taking down the tree and cleaning up my house and office (I even filed). Then, early Monday morning, I opened up my eyes and went, Eek. I have less than two months to finish What Remains of Heaven! I’ve spent the last two days rereading what I’ve already written and going over my notes for what lies ahead. It’s going to be close, getting this thing in on time. But with a few trips up to the lake and no more disasters, I think I can make it. And I had a great holiday. Happy New Year’s, everyone! Labels: writing, writing distractions

Writers Write

Writers write. At least, that’s what we’re supposed to do. But over the past month I’ve spent an extraordinary amount of time doing other things. To begin with, I’ve been reading galleys. For the uninitiated, galleys are photocopies of a book’s typeset pages. This is the author’s last chance to catch any mistakes—either their own, or those inserted by helpful copyeditors and careless typesetters. It’s always a nerve wracking and time consuming process, but when you have three books coming out in quick succession—THE ARCHANGEL PROJECT on September 30, the paperback of WHY MERMAIDS SING in October, and the hardcover of WHERE SERPENTS SLEEP in November—it can begin to feel as if it’s consuming your life. And then there’s the new C.S. Graham website. Even though we’ve outsourced the actual construction and design, I still had to decide on the exact look I wanted, find the images to convey that look, plot the site navigation, and write the text. That all takes TIME. And then there’s the week I spent filing. Okay, what was once an end-of-the year chore hasn’t been done since Katrina. But still. Being a writer generates enormous quantities of paper. Research notes and ideas for future books and royalty statements and contracts and transcripts of interviews and revision letters and on and on and on. I need a secretary. Just when I was about to tuck back into writing, I was told Steve and I have to do a Harper Collins’ “Microsite”. This is an ambitious project to put up mini webpages for all of HC’s authors. Of course, these are constructed to a strict template, and the template is designed for one author, not two (despite the fact that HC has a surprising number of writing duos). Headaches, upon headaches. Not to mention pages and pages of cute questions that needed to be answered. Like, “What’s your favorite item of clothing?” Or, “What would your dream vacation be?” It took me DAYS to come up with this stuff. Ironically, I learned some interesting things about my own husband in the process (“Your favorite food is grilled cheese sandwiches? Why didn’t you ever tell me that?”) But as I watched another week disappear without me writing one word on my book, I began to wonder, Is all this crap really necessary? Of course, in addition to being a writer, I’m also trying to get my house ready to move my mom out of her house and into ours, so the past month has also included a fair amount of cleaning and painting and packing and laying floors. Did I say, “writers write”? When?! Labels: galleys, promotion, writing

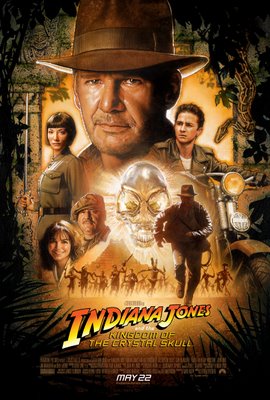

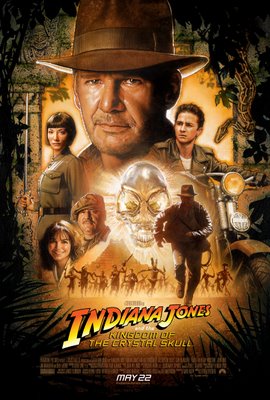

Indiana Jones and the Crystal Skull

I really, really wanted to love this film. After all, the first and third Indiana Jones movies are among my all-time favorites, and the producers did a great job of approximating the style of the earlier films. Harrison Ford handles his gently aging role with aplomb, as does Karen Allen. But this installment stumbles badly, and I think the ways in which it stumbles have something to teach writers. Warning: If you haven’t seen the movie, some of my remarks might be considered spoilers. But there’s nothing here I didn’t see coming a mile away. Which leads me to fault #1: Predictability. You might say this is an inevitable product of the genre, but I don’t think so. Remember those great reversal moments in THE LAST CRUSADE, when Sean Connery uses his umbrella to send up the seagulls and crash the plane? When we learn that Dr. Elsa Schneider is working for the Nazis? That she slept with the senior Dr. Jones? Or in THE LOST ARC, when the evil Gestapo agent holds up his palm to say “Heil Hitler,” and we see that the imprint of Marion’s medallion was burned into his hand? The fourth installment has none of those moments. Stereotypical characters. CRYSTAL SKULLS has a character who is sort of a compilation of Sallah, Belloq, and Schneider. Needless to say, he doesn’t work, and I had to look up his name before I could even remember what it was (Mac). I have read raves of Cate Blanchett’s depiction of her character, Irina Spalko. Perhaps she did the best she could with what she had to work with, but in my opinion, her character hit one evil note and held it through the entire movie. She wasn’t interesting, she wasn’t fun, she was just…a stereotype. Yawn. The interaction between Indie and the boy, Mutt, had some good moments, but I kept thinking they could have done so much more with it, while the bits with Marion were so hackneyed and clichéd they made me squirm. Plot development. Nothing much happens in this movie. It felt like half of the screen time was taken up by one long chase through the jungle. And while it was fun at first, it eventually just felt…long. Plus, while it may be a Hollywood convention to have the bad guys shooting endlessly at the good guys and still missing, this scene was by far—BY FAR—the worst I have ever scene. It went beyond improbable or silly, and just became hopelessly contrived. And boring. Because if they’re that bad of shots, there’s no danger, right? Plot holes. Where does one start? Like, why did the American government need an archaeologist to help them deal with an alien? Or, why were those conquistadores buried in a tomb with all their loot? I could go on and on and on, but I won’t because it would give too much away. All I’ve got to say is, They take twenty years to write a script, with the “best” people in Hollywood working on it, and they can’t do better than this? But the most damning flaw in the entire movie was this: Lack of a powerful forward thrust. It could have been there—it should have been there—but it wasn’t. At one point—I believe it was when they were crawling around in the cemetery—I actually found myself thinking, “Now, what are they here for again? What’s the whole point of this movie?” Ouch. Labels: Crystal Skull, screenwriting, writing

A Story with Two Legs

Mark Truby’s THE ANATOMY OF STORY has, I am told, become the new Bible of screenwriting. I’ve been slowly winding my way through it for some weeks now. This is not a fast, easy-to-grasp read. He devotes vast chunks of his book to topics like Moral Dilemmas, and Symbol Webs, which tend to give me squirming flashbacks to my college English class. (The only “B” I ever got in eight years at university was in Freshman Creative Writing. I kid you not.) But the section I’m reading now, on Plot Types, has much meatier stuff. Truby sees a story as moving toward its character’s desire on what he calls two “legs”: acting and learning. Basically, a story is about how a character takes action to get what he wants, and the new information he learns about better ways to get it. As a result of the new information he acquires, he makes a decision and undertakes a new course of action. Some story forms highlight one of those “legs” over the other. Myths and action stories focus on, well, action, while mysteries and romances tend to highlight learning. Truby identifies a number of different plot types emphasizing one or the other of these “legs,” including the Journey Plot, the Three Unities Plot, the Reveals Plot, the Antiplot, the Genre Plot, and the Multistrand Plot. Ever since THE HERO’S JOURNEY became popular a few years ago, there has been a tendency—especially among romance writers—to try to jam every plot into the mythic journey form. I’ve always though that was stretching the myth form to the breaking point, although, obviously, that approach works for some authors. Because in the end, these are all simply mental constructions we use to make our job a little easier. As I work my way through Truby, I’ll be talking about his ideas some more. This week I’ve been focusing on 1) getting my youngest home from her Florida college alive (she spent all of Wednesday in the Emergency Room); 2) getting the main bathroom remodeling finished (not going to happen before the youngest comes home from college); and 3) getting the new C.S. Graham website up (a long process only just begun). Labels: Mark Truby, screenwriting techniques, writing

Now That’s Scary

It’s every writer’s worst nightmare: their precious, hard-wrung words, over which they’ve sweated blood and tears for months and months, gone in the blink of an eye—or rather, in the click of a mouse. That’s what happened this week to John Connolly. If you’re not familiar with John Connolly, he’s an Irish writer of lyrically beautiful thrillers. If you are familiar with John Connolly, then you’ll probably want to weep when you hear he just zapped the first 30,000 words of his next book into oblivion. How? He was moving the most recent chapters of his WIP (“The Lovers”) from his laptop to his desktop computer, and accidentally overwrote the original file containing the first section of the book. Click. Gone. Normally, he backs up his work as he writes. But life has not been normal for John lately. He’s just moved house. He just came back from an extended trip to the States. And, it seems, he does not print out on paper as he writes. So all is truly lost. We hear these horror stories every so often. A thief who steals both computer and backups. A fire that destroys all. A computer that crashes and can’t be resuscitated. A friend here in New Orleans lost practically an entire manuscript to Katrina’s floodwaters. Time now for us all to take a good, hard look at our own writing/backup practices. I do print out my chapters as I write them; I have never, ever trusted computers, or myself with computers, and I like to hold a manuscript in my hand. But I am still terrible, just terrible, about backing up as I write. I’ve now set up a separate email account, and hope to get in the habit of emailing myself my output for each day. As for John…he’s called in a computer expert, but the prognosis is not good. Labels: John Connolly, writing

Historical (In)Accuracy

I recently read two historical novels, one brilliantly researched and wonderfully historically accurate, the other…not. Because the novels were set about 50 years apart, and because I read them back-to-back when I was sick, the experience left me thinking about historical accuracy, historical inaccuracy, and reviewers and readers’ ability to recognize the difference. The first book, HONORABLE COMPANY by Allan Mallinson, is set in India before the Raj and forms part of a fascinating series detailing the varied adventures of British Dragoons officer Matthew Hervey through the years following the Battle of Waterloo. A serving cavalry officer in the British Army, Mallinson is also the author of LIGHT DRAGOONS, a history of the British cavalry. This guy knows his stuff, and what he didn’t know has been painstakingly researched. The second book, from a historical mystery series set in the 18th century, is by a NYT bestselling American author who has branched out into the mystery field after penning a wildly popular romance series set in the same period. Her hero is the younger son of an earl and also an Army officer. Although the author—whom I’ll call “D”—has no professional training or experience, she prides herself on her “thorough” knowledge of the 18th century and frequently brags that she does all her own research. Reviewers and readers consistently sing her praises for her historical accuracy. So it was something of a shock when I began reading her book and found myself tripping over one anachronism after another. I’m not talking about tangential, nitpicky little things only a specialist would detect, but the kind of information many absorb simply by reading—or by being born English. For instance, most readers of Dorothy L Sayers (and Georgette Heyer) know that Lord Peter Wimsey is called “Lord Peter” because he’s the younger son of a DUKE; if he were the younger son of an earl (like “D”’s hero), he’d be just plain Mr. Wimsey. Likewise, if “D” had ever read Allan Mallinson’s Matthew Hervey series, she’d know that officers of the lowest rank in the British Army in the 18th century (until 1871, actually) weren’t called second lieutenants; they were cornets. And if someone is writing a book set in mid-eighteenth century London, why are they using (as “D” proudly announces in her author’s note) Greenwood’s 1837 map of London? London changed dramatically in those eighty years, and earlier maps are readily available. I could go on and on, but I’ll restrain myself. The point is, why is this author praised for her historical accuracy when her stories are so painfully INaccurate? I’m beginning to realize that all a writer needs to do to gain a reputation for “thorough research” and “knowledge of the period” is to look at a couple of history books on their subject, salt their writing with strategically lifted tidbits and details, and then tack on an Author’s Note listing a few resources. We saw the same thing happen with Dan Brown, who made hilarious mistakes in both Angels and Demons and The Da Vinci Code, but because he included long passages of info dumps lifted (sometimes verbatim) from nonfiction sources, still managed to fool legions of reviewers into calling his books “exhaustively researched” and “intelligent.” Ironically, many readers also think they “know” things about a period that they don’t, and will therefore criticize a writer for making mistakes that aren’t mistakes at all. I’ve seen it happen to other writers, and it happens to me. Don’t get me wrong; I make mistakes, too (such as, ahem, mentioning a certain dog breed in Why Mermaids Sing that wouldn’t come into being for another twenty years). But a more in-depth knowledge of a period can, ironically, work against an author, if their knowledge of everything from the state of the Thames in 1812 to early nineteenth century social and intellectual history runs counter to common perceptions. If I’m sounding a bit disgruntled, it’s because I am. A writer without any real knowledge or understanding of a period can write fun "historicals" that satisfy many readers. That’s fine. But why proclaim an authenticity and expertise that doesn’t exist? True knowledge of a historical period or subject requires more than a few lurid details culled from a couple of reference books. There is also a difference between knowledge of period details and the kind of true UNDERSTANDING of a period and culture that can only come from a more in depth study. A writer doesn’t need to be an historian to achieve this; Allan Mallinson is an Army officer, not an historian. But he knows what he’s writing about, he doesn’t take shortcuts in his research, and it shows. Labels: history, market research, writing

Stalin’s Ghost

It’s been 26 years since Martin Cruz Smith wrote GORKY PARK and first introduced the world to Arkady Renko. His latest Renko book, STALIN’S GHOST, is only the sixth in the series. Books like this cannot be rushed. Smith writes intriguing mysteries with page turning suspense, but they are also so much more. The prose is brilliant, the characters memorable, the descriptions and atmosphere haunting, the stories thought-provoking and enriching. In short, these are stunning works of literature that also happen to be cracking good reads. An all-too-rare combination. One of the aspects of this series I particularly love is the way Smith has used Renko to illustrate the profound changes that have rocked Russia in the past two decades. In Gorky Park we saw the painfully honorable and ethical Renko struggling for justice in the crazy, upside down world of a moribund and corrupt Soviet regime. Polar Star (my personal favorite) brought us a disgraced Renko trying to survive as the Soviet world collapsed around him. By the time of Red Square, Russia is being torn apart by criminals and capitalism at its most ruthless and destructive. Wolves Eat Dogs, set in Chernobyl, shows us a Russia ravaged by billionaire oligarchs. Now, in Stalin’s Ghost, we see a Russia whose battered citizens are yearning for the glory days of the past while the secret police and Special Forces begin to reassert control. Through it all, Arkady emerges as one of literature’s great characters. He may be brilliant, but he is not always wise, for in Russia (as in the US), an ethical man truly dedicated to justice will soon fall afoul of the system and his superiors. Once alienated from and disturbed by the coercive, mind-numbing form of Communism implemented in the Soviet Union, Renko is now troubled by the rampant greed and human toll of unbridled capitalism. Loyal to his friends and those he loves, he views the foibles of the world around him with a black wit that makes for highly entertaining reading. I have one Smith book left—December 6, a historical set at the outbreak of World War II. I’ve been stretching his books out, savoring them in between lesser reads. He is a true master, with much to teach aspiring writers. If I get my thoughts organized, I may make that the subject of a future blog. Labels: Martin Cruz Smith, Stalin's Ghost, writing

When a Character Won’t Gel

This isn’t a problem I have often, but I’m wrestling with it now: the antagonist in my current WIP (Work in Progress, i.e., THE DEADLIGHT CONNECTION) just won’t come to life. He lies there on the page, a pale dull reflection of nothing. Why? I’m not sure. The character in question is an Army general. Now, I know military men. For heaven's sake; my father was an Air Force colonel and I’m married to a retired Army colonel. But this character is also hyper-religious and a racial bigot. And while I’ve known a fair share of people like that, too (although not, fortunately, too intimately), for some reason my General Boyd just won’t gel. I spent most of yesterday trolling the Internet, reading some truly scary stuff written by some truly scary people out there. Rabid evangelicals (with ready White House access) who think the End Times are upon us and all they need to do to help things along is go nuke Iran. People who homeschool their kids to protect them from the evil influences of biology classes and then send them to colleges where students pledge not to KISS until they’re married. People who drip hatred and ignorance and vile prejudice (many of them also with White House access). And still the General lays there, an illusive cardboard figure. I’ve developed his background (for my own usage; most of this stuff never sees the light of day). I know all about his childhood. His rowdy, beer-drinking youth. His decision to “take Jesus Christ as his personal savior”. His marriage and his six kids. And still he lies there on the page, hollow and wooden. Bookstores are full of popular thrillers with silly, unreal villains. I keep telling myself, Most of your readers will neither notice nor care. But some will. And I will. Labels: creating characters, writing

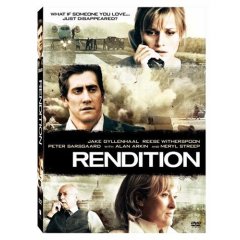

Rendition

I wanted to see this movie when it was in the cinemas, but it came and went too fast. Given its lukewarm reviews, I almost didn’t even bother to rent it. Which would have been a shame, because it is actually very well done. No, it’s not a perfect film. But it is a very good one. The story is the kidnap and torture by the U.S. Government (in a process know as “extraordinary rendition,” begun by Bill Clinton back in 1995 and seriously kicked into high gear by W) of an Arab-American, and how it effects not only the victim, but also the victim’s family, the CIA personnel involved in the crime, and the Washington politicians who must choose between their consciences and their political careers. There is also an entwined love story involving a young Arab woman and man (the exact North African country involved is never named), and the young woman’s father. This subplot initially annoyed me, but in the end it dovetailed beautifully and added tremendously to the film’s depth and power. (Because almost anything I could say would be a spoiler, I won’t even address that aspect). Omar Metwally, who plays the victim, Anwar El-Ibrahimi, deserved an Oscar for his brilliant portrayal of a terrified, bewildered, angry, and—ultimately—broken man. Yet this film is not so much about the hapless young chemical engineer who is brutalized, but about the moral choices made by those around him. This seemed to bother some viewers, who require a single hero/heroine they can follow and “get to know.” The whole moral choice thing evidently went over their heads. Some found the entire situation “unbelievable;” cognitive dissonance strikes again. Others complained about the “liberal bias” of the film, which i found really scary. When the assumption that torture is morally repugnant is denigrated as liberal bias, you know a culture is in trouble. As a writer, I can usually see the twists and climax of a movie coming a mile away. Not so with this film. The suspense came not simply from the question, Will El-Ibrahimi be saved? but also, How far will the torturers go? If El-Ibrahimi is saved, will he be irreparably damaged? Of the various characters faced with a moral choice—the CIA agent played by Jake Gyllanhaal, the Senator played by Alan Arkin, the Senator’s aide played by Peter Sarsgaard, the Muhabarat officer played by Yigal Naor—will any of them rise to the occasion? Or will they all travel down the path of moral abdication taken by so many before them? This is not a film to watch and forget. I found myself wanting to know what happened to the various characters AFTER the film was over. Did Character X suffer for his decision? What happened to Character Y? And so on. Which, as far as I’m concerned, is the hallmark of a successful film well worth studying. Labels: Rendition, writing

Sneering Heroes

I’ve been limping through a book by a NYT bestselling writer for about three months now. Obviously I’m not enthralled, so why am I still reading it? Because I like to be familiar with the various well-known thriller and mystery novelists out there, and that means reading at least one of their works. There is much to like about this book. The author—I’ll call him “h”—has a breezy, conversational style that makes for a fast, engaging read. On the other hand, his style is so conversational that he frequently skips back and forth between past and present tense—even in the same paragraph—which repeatedly jerks me out of the story and drives me nuts. But what has really turned me off on this writer is the fact that his hero sneers at everyone around him. The book is told entirely from the hero’s point of view, and no one—not his dead wife, not his mother, not his sister, not his best friend, not his father-in-law—no one is portrayed as an attractive, sympathetic person except for our hero. He sneers at everyone. I was commenting on this to my Monday night writers group, and Sphinx Ink—who has a far better memory than I do—said, “I remember you complaining about another writer for the same thing.” I said, “I did?” So I did. That book—by a former romance writer turned thriller writer whom I’ll call “t”—featured a female protagonist who also sneered at all around her. It was a big book with a huge cast, and the only person our heroine portrayed kindly was an eight-year-old kid—and maybe a horse. I mention the horse because there were two dogs and a cat in the story, and they were also portrayed as unpleasant beings. So what’s going on here? As writers, we’re frequently told to create a “sympathetic” protagonist—someone our readers will “like.” Personally, I don’t like people who sneer at everyone else, but since these writers are on the NYT bestseller list, I’m obviously alone in finding their work offensive. Another member of our group, Charles Gramlich, who in addition to being a horror and fantasy writer is also a psychologist, said he thought a lot of people actually enjoy seeing other people put down—that this is a big part of the appeal of Reality TV and shows like Candid Camera and Survivor. What do you think? Labels: characterization, writing

The Hundred-Page Hiccup

I’ve been at this writing business long enough that I’ve begun to notice a pattern. Not in every book, but in enough of them that I’ve learned not to panic (too much), somewhere around about page 75 to 100 I find I frequently start getting uncomfortable with the way a manuscript is progressing. If I were a pantser I guess I’d just charge ahead and finish the book, figuring I’ll go back and fix it on my second pass. But because I have this thing about control, I can’t do that. I also have this fear that what’s wrong may be so fundamental that I need to fix it now before I get irretrievably headed off down the wrong path. So I go back and reread. And fret. And reread. And struggle to figure out why things just don’t “feel” right. Eventually, I have a eureka moment and I realize out what’s wrong. Sometimes it’s a plot problem. Sometimes it’s a problem with character development. In the book I’m working on right now—my second thriller, THE DEADLIGHT CONNECTION—I knew that for a three to four chapter stretch, the book was going flat. Why? It wasn’t a plot problem—those scenes were pivotal. So why did that section feel off? I finally realized that in that section I was forgetting to make my scene questions clear. I was also failing to add the necessary depth to my character’s experience. Now that I know what the problem is, I’ll go back and rework. Only then will I be able to move forward again. Until I hit the next hiccup. Labels: revisions, writing

Cardiopulmonary Reality

You know the tendency some authors have toward filling their thrillers and romances with pounding hearts and quickened breathing? I once heard a great expression for it: cardiopulmonary hyperbole (I wish I could acknowledge where I got this gem, but I’ve forgotten). It’s an easy trap to fall into because, how else do you describe the human reaction to fear? Last night, I was stopped at a red light at the corner of Vets and Transcontinental here in Metairie when I saw a blue minivan come barreling up behind me, swerve into the turning lane, and shoot on out into the intersection. In the slow motion way these things happen, I had time to think, “That idiot is going to run the red light,” and, “Oh my god this guy’s going to get hit,” before a car going about 45 mph slammed into him. The impact flipped the minivan and sent it airborne. As I sat there watching this upside down minivan flying through the air toward me (and my shiny new red car), my thoughts naturally turned to, “Eeek, this guy could come down right on top of me!” and “There’s a car behind me, I can’t back up.” Then the minivan crashed down on its roof a few feet in front me and skidded to a halt beside me. Without the least danger of falling into hyperbole or exaggeration, I can quite accurately say that my breath was coming hard and fast. I punched on my emergency flashers and watched incredulously as the guy behind me calmly pulled out into the turning lane, passed me, and continued on through the intersection when the light turned green. No cardiopulmonary excesses there, obviously. Everyone else in the vicinity was spilling out of their cars, yanking out their cell phones (of course I didn’t have mine), and screaming, “Oh, my God! Oh, my God!” Writers are sick people. Yes, I was horrified by what I had just seen happen to the occupants of that minivan, and humbled by what almost happened to me. But a part of my brain was also thinking, “Hmm. My heart actually isn’t pounding all that hard, but I am seriously hyperventilating. What other physical symptoms of shock and horror am I experiencing? How would I describe them?” The problem is, of course, that these are the standard human reactions to fear and shock—pounding heart, rapid breathing—and there are only so many ways to describe those physical manifestations. The secondary reactions set in a few minutes later—the shaking and (for those of us with a tendency to cry) the tears. So how do writers of books filled with shootings, explosions, chases, etc, avoid falling into cardiopulmonary hyperbole while still giving readers a realistic description of the effect of these incidents on their characters? Labels: descriptions, writing

Five Writing Strengths

Shauna Roberts at For Love of Words tagged me for this deadly meme: identify five of your writing strengths. I could have come up with five of my writing weaknesses in a heartbeat. But strengths? It’s taken me a couple of days, but here it is: 1. Characterization. This is something I do purely by instinct. I sit down to write and strange, wonderful, distinct, well-rounded people simple come to me out of the ether, surprising me. I could never give a presentation on characterization because I don’t know how to do it. I just do it. 2. Plotting. This is something I do not do by instinct. Back in my prepub days, I asked a published author I respected what she thought was my greatest weakness as a writer. She said, “Plotting.” Stung, I read everything I could on plotting. I analyzed well-plotted books and badly plotted books. I thought long and hard about plotting. It’s now one of my strengths. I could talk your ear off, telling you about plotting. 3. Hard work. See #2 above. I am willing to work very, very hard to make a go of this writing thing. I research my books to death. I study writing and writers. I constantly analyze the market and why people read what they read. I preplan and rewrite. If I have to change—whether it requires changing genres, or even changing the way I write—I will. I write two books a year, which is really, really hard for someone who’s not naturally prolific. There are lots of other things I’d like to do in my life—paint, learn to play the guitar again, read more, travel more, sleep more. I take care of my family, and I work. 4. Versatility. I’ve written and sold romances, contemporary thrillers, and mysteries. They are all very different, requiring different skills and calling on different parts of my personality. It has helped me grow tremendously as a writer. 5. My background. As a historian, I bring to my stories a strong, in-depth understanding of various historical periods and trends. I’ve lived in and traveled to lots of different places, so I can draw on that, too. And I’ve done many different things in my life—ridden camels, fired flintlocks, fenced, survived volcanic explosions, hurricanes, riots and revolutions, spent years training in tae kwan do, worked on archaeological digs all over the world—and a few other things I’d rather not mention!—that I can call on when I need them to enrich my stories. Any one else willing to do this? Steve? Charles? I warn you, it’s hard! Labels: writing

Readers Guides

My publisher recently suggested I draw up a Readers Guide for WHY MERMAIDS SING, my next Sebastian St. Cyr mystery. As you know, Readers Guides are those lists of questions intended for book clubs. I belonged to a book club once—for two and a half months. We read THE INSTANCE OF THE FINGERPOST and THE QUINCUX. I struggled manfully (womanfully?) through both. I forget now what the next month’s selection was, but I decided the book club scene was not for me and withdrew with politely murmured excuses about time. We weren’t a particularly organized book club, so we didn’t use Readers Guides. If we had, I would have left after two and a half minutes. Nevertheless, having received my assignment (publisher’s suggestions are generally treated like commands), I Googled “Readers Guides” and set about looking at some examples. Yikes. (If you yawned through any college lit class, you can skip these examples and go straight to the next paragraph.) Consider this from THE LIFE OF PI: “Yann Martel sprinkles the novel with italicized memories of the "real" Pi Patel and wonders in his author's note whether fiction is ‘the selective transforming of reality, the twisting of it to bring out its essence.’ If this is so, what is the essence of Pi?” Oh my God! Then there’s this example from THE DUEL: “Like much of Russian literature from the nineteenth century, The Duel deals explicitly with ideas and ideologies and how they function in the ‘real world’ depicted in the novel. Chekhov’s story plots the conflict between two protagonists who espouse antithetical worldviews: Von Koren and his Social Darwinism, in which only the fittest should survive, and Laevsky and his “Hamletism” (“My indecision reminds of Hamlet”), that is, his tendency to blame his own hypocrisy and moral turpitude on the corrupting influences of his time and civilization. Identify and discuss some of the passages in which the two characters discuss their own and, more important, each other’s worldviews. In what ways do these two protagonists embody their self-professed beliefs?” Okay, maybe Chekov was a bad choice. I keep looking, and find this: “I’m Not Scared is preceded by an epigraph by Jack London: ‘That much he knew. He had fallen into darkness. And at the instant he knew, he ceased to know.’ Why has Niccolò Ammaniti chosen to begin his novel with this quote? How does it illuminate what happens in the story? What is the literal and symbolic significance, in terms of the novel, of falling into darkness?” Are you running screaming for the door yet? These are the kind of questions that make college kids think they hate fiction. But I tried. I tried to come up with questions that wouldn’t make a reader’s eyes glaze over, that would perhaps stimulate some positive thinking about my book. I sent them to my editor this morning. Her response? “If they remind you of an English class then maybe they’re boring questions. Try to come up with the kinds of questions a group of women sitting around with coffee and cookies would like to discuss, something that relates the story to their own lives.” Um. Okay. How about… “How would you react if you found a partially butchered body with the severed hoof of a goat in its mouth? Compare and contrast your reaction with Sebastian’s.” Or maybe… “How would you feel if you discovered you were sleeping with your sister?” Somebody just shoot me now. Labels: readers guides, writing

When Bad Things Happen to Good Writers, Part One

I’m about to tell two stories that are, sadly, only too true. I tell them as a warning to all who think they really want to get into this crazy publishing business and as a reminder to those who are already here to always, always look a gift horse in the mouth—at least when the gift horse comes from a New York publishing house. Our first story stars a writer we’ll call Annie. Annie is (or maybe we should say, was) an up and coming writer of historical romances. She’s a smart lady, having earned a PhD in an earlier incarnation, and she’s been at this writing business for enough years that she was starting to attract some serious attention. She wrote for a strong house with an enviable reputation for putting even mediocre romance writers on the Times. She hadn’t exactly “made it,” but things were definitely looking good. So what happened? Well, an editor from a rival House That Shall Not Be Named heard Annie was up for contract and approached Annie’s agent with a wonderful offer. The HTSNBN would give Annie a three-book contract at twice the advance she was making from her previous house. Not only that, but they also promised the moon and the stars, in the form of co-op (if you don’t know, that’s the money publishers pay to get an author’s book displayed at the front of stores) and oodles of promotion. Flattered and flush with visions of her imminent success, Annie switched houses. So what happened? The HTSNBN didn’t provide either the promotion or the co-op. Without these inducements, advance orders were thin. The print run for her first book with the HTSNBN was smaller than her print runs with her old publisher. There was no way this book was going to come even close to earning out its stellar advance. Frightened by the hemorrhaging red ink, the HTSNBN gave Annie’s second book an even smaller print run, and if the print run for her third book had been any smaller, it’d have been a negative number. At the end of her three-book contract, the HTSNBN dropped Annie. Annie now has no contract and “numbers” that are in the toilet. Through no fault of her own, her career is perilously close to being ruined. Why did the HTSNBN do this to Annie? I don’t know. It’s just weird. After all, they approached her. They should have known that without the co-op and other promotional activities they’d promised, there was no way her books were going to earn out a high advance, yet somewhere along the line they made the decision to yank their support and simply throw her books out there to disappear into the ether. It’s tempting to think, “Well, maybe she turned in books that weren’t as good as they expected.” But that isn’t it. The sad truth is that Annie’s story is unbelievably common. I’ve seen something similar happen to my sister (Penelope Williamson), to me, and to more writers than I could name. And it isn’t just the publishers you need to watch out for. You also need to be wary of bookstores. That’s right, bookstores. But that's for Part Two… Labels: career, writing

Punch It Up

We all know the “rule”—that the last sentence of every scene, like the last sentence of a chapter and the last sentence of a book—needs to be powerful. This is a concept my writers group has been kicking around for a while, and we’ve realized the same thing is also true of paragraphs. The more wallop packed by the last sentence of every paragraph, the more effective the writing. And then we noticed something else—the last WORD in each paragraph needs to carry a punch. We looked at a poem written by Charles (which happened to be handy at the time we were discussing this). The last words in his stanzas were evocative words like misery, peril, aura. Then we looked at a poem by another writer. The last words in his stanzas were pedestrian words like it, them, then. The difference was startling. It might be more noticeable in poetry, but the same principle applies to prose. Yes, there are times the humdrum word choice can’t be avoided, or when the flow and cadence require the invisible “said.” But glance through a few novels, just looking at the final words in the paragraphs, and you’ll quickly notice the difference. I pull SUNSET LIMITED by James Lee Burke from my shelves and I see paragraphs ending with words like fingers, skin, heat, stars, breathe, glow, porch, bone, scrawl. I look at a bestselling thriller written by a former romance writer and see sentences ending with words like him, it, is, to, out, up, out, here, well, that, on, down, had. This is something the best writers do instinctively. But it doesn’t hurt to be aware of this concept. It’s one more tool that can be brought into play at the revision stage, when you know a passage doesn’t “feel” quite right or lacks the necessary punch. Look at the last words in your paragraphs. Labels: craft, writing

Revisiting Hell

The galleys for WHY MERMAIDS SING are due back in New York on Tuesday. Because of the long time lag in publishing, that means I’ve been spending the last few days rereading the book I wrote right after Katrina—the book I thought would never get finished. I had sent the proposal for MERMAIDS off to my agent right before the storm hit. And then I didn’t write another word for more then six months. At first my days were spent driving back and forth from Baton Rouge, mucking out the house, dragging what couldn’t be salvaged out to the curb, tearing out walls. Even after we moved down to my mother’s house in Metairie, we still had to drive up to Baton Rouge once a week for groceries. While we waited for our stripped studs to dry out, I set about the painful task of attempting to restore my antique furniture. And then it was time to start putting up walls, finish Sheetrock, and do all the million and one other things needed to put a house back together. I spent my days in paint-splattered clothes, joking that with the cost of labor in New Orleans I could make more money installing Sheetrock than I could writing. Actually, it wasn’t a joke. After all, the only reason I’d acquired the skill was because good Sheetrockers were impossible to find in New Orleans. They still are. But I digress. Sometime around February or March I realized I had to quit working on the house and start working on my book. My deadline was looming. Only, how could I? We were rebuilding the house ourselves simply because we couldn’t find anyone to hire. Even putting in 12-14 hour days, Steve could only do so much on the weekends; I was the one working on it seven days a week. I was desperate to rebuild my nest, rebuild some kind of normal life for my traumatized chicks. I kept saying, how can I just quit and sit down and start writing? How can I write when I live, breathe, sleep, dream Katrina? In the end, of course, I realized I had no choice. At first I set up my computer in my mother’s backroom. Then Steve and our friend Jon got the paneling up in my office and I started writing in here. The floor was just a concrete slab, there were no baseboards or crown moldings or doorframes or window frame (actually, there’s STILL no window frame!). There was no kitchen in the house, although one of the bathrooms upstairs still functioned. The neighborhood was filled with the sound of air compressors and hammering and sawing. I kept saying, I can’t write like this! I’d write half the day, then give in to the compulsion and go off to do Sheetrock or sand trim, seal tile or paint ceilings. In the end, the only thing that saved me was the miracle that is the lake house. Yet somehow, the book not only worked, but worked amazingly well. The only problem is that as I go through the galleys, I find that I can only read about thirty pages at a time and then I need to put it aside and do something else for a while. I find myself remembering the time I was assaulted by a raving lunatic at one of the city’s few functioning gas stations (people were seriously losing it in those days). I remember sitting next to my dying aunt and listening to the hospital rep apologize for the fact they were using orange FEMA blankets, but their laundry service had flooded. I remember the miles of flooded cars choking the streets of New Orleans, the boat abandoned just two blocks from my mother’s house (where the water stopped). I remember the huge flies that seemed to mutate after Katrina, and the smell. Who could ever forget that smell? And then I go pick up the galleys again. And I wonder, is it there? Did the heartache and the trauma and the craziness of it all somehow bleed into these words about an English Viscount chasing a tormented killer through the streets of 1811 London? I don’t know. Labels: Katrina, Why Mermaids Sing, writing

Skiing Off a Cliff

There’s one thing to be said for skiing off a cliff or being broadsided by a truck. Apart from giving you a new appreciation of how quickly life can go spinning out of control, it definitely tends to shift your perspective. I was ruminating on those life experiences Monday as I was flying down the interstate at 85mph (hey, this is Louisiana). And because I’m a writer—which means I’m always seeing analogies even where there aren’t any—I thought it might hold the key to why I manage to get so much written when I’m up at the lake. There are all sorts of prosaic reasons, of course. No internet. No piles of laundry and dirty refrigerators beckoning to be cleaned out. The freedom to listen to my inner body clock, which means scribbling away until 4 am and sleeping guilt-free to 10 or 11. And then there’s the blessed sound of silence, and the soul-lifting inspiration that comes from the sight of sun glistening on breeze-licked waves. Those are all, obviously, contributing factors. But I suspect a major key to my uncharacteristic prolificacy up there is that going to the lake yanks me out of my routine everyday patterns. It shakes me up, breaks my habits, sets me free to be different. Cocooned alone in the lake house, I can immerse myself in my story and then simply let it flow out of me. When I want a break, I go walk around the lake or grab a paintbrush. But the story stays with me. In me. My world becomes the lake and my story. I have a friend who has written all twenty of her books in longhand while sitting in a coffee shop. The other day I told her I thought maybe she had something there, that I’d noticed I’m actually far more productive when I’m up at the lake and writing by hand. You know what she said? “Really? I’ve just started composing at my computer because it seems faster.” Of course it is, theoretically, since one eliminates the step of having to type up what one has written. It’s why I shifted to composing at the keyboard years ago. But I suspect she’s feeling a burst in her productivity largely because her process is now different. I can still remember the heady days of the first book I ever wrote, scribbling by hand, dashing after my story with no outline and little forethought. Over the years—I’ve been at this twenty years now!—I’ve learned how to do so many things so much better. But in the process something was lost. Something I recapture—at least partially—sitting on that porch swing with a notebook propped on my lap. So here’s to being shaken up—preferably in a nonlethal way. If you normally compose at your computer desk, go sit out under a tree and write by hand. If you outline, ditch it for a day. If you don’t outline, try it. Light candles and play Gregorian chants. Or douse the candles and turn off the CD player. Get up at 5 am and write while you watch the sun come up. Or write by moonlight in the stillness of the night. Why wait to be clobbered by a hurricane to try something different? Labels: writing

|